This site uses cookies, as explained in our terms of use. If you consent, please close this message and continue to use this site.

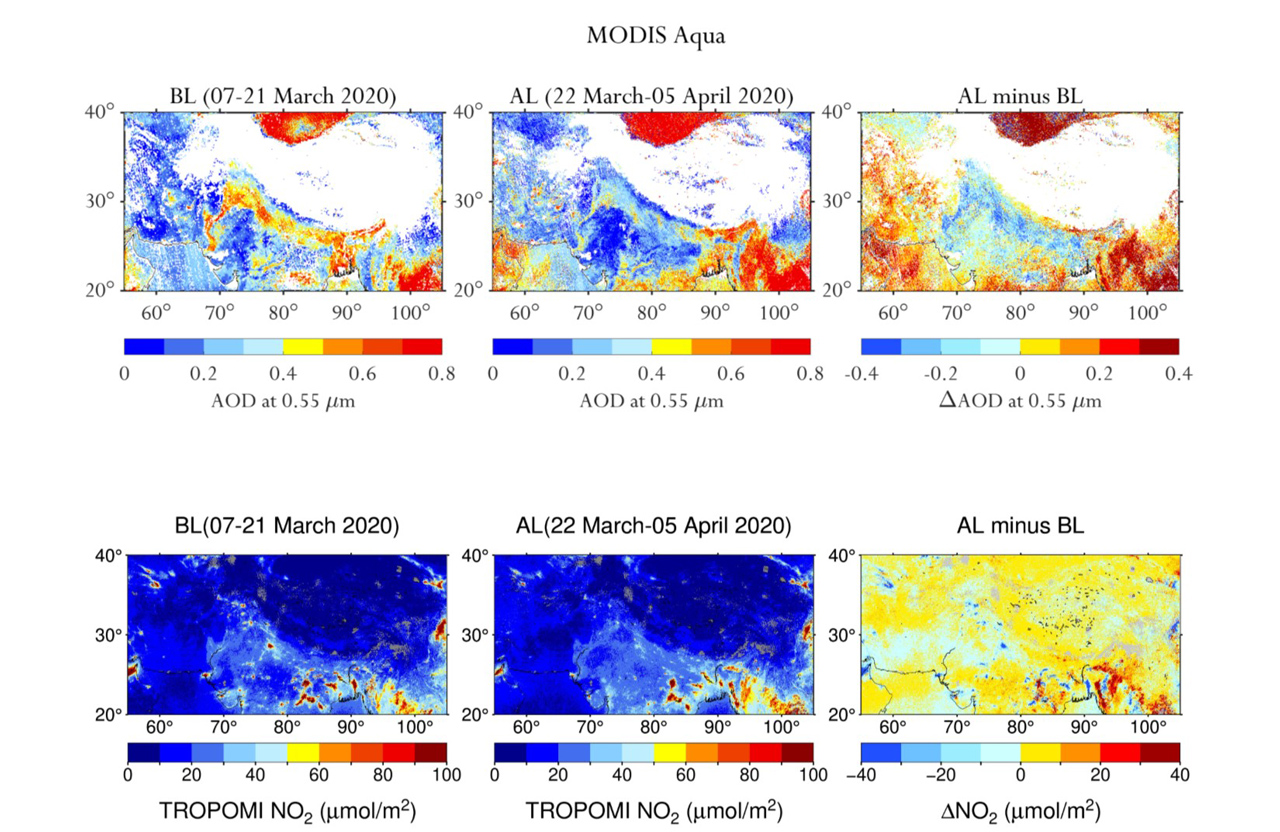

Top panel shows aerosol optical depth (proxy for particulate loadings) before and two weeks into the lockdown period derived from MODIS instrument onboard the Aqua satellite. Bottom panel shows column NO2 concentration derived from TROPOMI instrument onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor (Sentinel-5P) satellite during the same time period. Figure credit AOD – Pravin Singh, NO2 Sishir Dahal

Top panel shows aerosol optical depth (proxy for particulate loadings) before and two weeks into the lockdown period derived from MODIS instrument onboard the Aqua satellite. Bottom panel shows column NO2 concentration derived from TROPOMI instrument onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor (Sentinel-5P) satellite during the same time period. Figure credit AOD – Pravin Singh, NO2 Sishir Dahal

The lockdowns across the Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region have resulted in perceptible improvements in air quality and visibility across the region. Is this because of lower emissions or favourable meteorological conditions? The overall picture is not so clear, as Bhupesh Adhikary, our Senior Air Quality Specialist explains in this interview.

1. We wanted to speak with you today about air pollution in our cities and the HKH region as a whole. Can you tell us what you have observed and what the data says about the period immediately after lockdowns were imposed in many parts of the HKH region?

Before we look into what happened after the imposition of lockdown, we need to understand the climatological context of air pollution during this time of the year. Air pollution is usually high in the pre-monsoon (March, April, May) season in the HKH region. This is primarily due to open burning of crop residue and yard wastes throughout the region, in addition to forest fires. This emission, which is seasonal in nature, happens in the months of March and April. The concentration of many air pollutants is often almost double during this time of the year at many places. The meteorological conditions are also favourable for pollutant transport from the foothills and Indo Gangetic Plain (IGP) to mountain cities and villages during this time of the year.

If we analyze the surface PM2.5 data from March to April across cities and towns in the HKH, while we do see reductions, the reduction is not uniform across the region. Megacities within our region have seen a significant drop of pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide, which mainly comes from the transport sector. Aerosols over the IGP (as inferred by AOD measurements) have also significantly declined. Other pollutants such as surface ozone do not show significant decline based on the limited data that is available.

Our preliminary analysis of the early lockdown situation is based on the data available from satellites and limited ground-based surface air quality measurements in the region. Surface air quality PM2.5 measurement data from Afghanistan to Myanmar (from the west to eastern HKH) does show decline when comparing two weeks before and into the lockdown. Some megacities such as Lahore, Delhi, and Kolkata show significant reduction in PM2.5 concentrations in these periods. However, observatories in Kathmandu reported higher PM2.5 than before, indicating stronger local emissions. The data further shows that during the early lockdown period PM2.5 concentrations were comparable to concentration levels during prior monsoon periods over the western HKH, while the same is not true over central and eastern HKH during the two-week periods before and into the lockdown. The surface PM2.5 concentrations over the eastern HKH region were higher possibly due to open fires in the eastern region at the time. PM10 data from Kathmandu shows significant decline when compared to the period before the lockdown. This reduction has also resulted in greater visibility within the valley.

Later into the lockdown period, we have had substantial pre-monsoon rainfall, which complicates the attribution of the reduction to lockdown only versus reductions due to meteorology.

2. What do you think are some potential sources of the air pollution which continues to persist in the region?

As mentioned earlier, crop residue and yard waste burning is a major source, along with seasonal forest fires. This will begin to subside once the monsoons come. What we also need to understand is that other than industrial and transport sectors, emission from the residential sector is by far the most important sector for majority of air pollutants in the eight HKH countries. Current lockdown restrictions on mobility has had profound impacts on the emissions from the transportation and industrial sectors globally in the short term. The same is also true for our the eight HKH countries.

Emissions from other major source categories, such as energy production, agriculture and municipal waste, have not seemingly changed significantly compared to annual emissions, at least in the short term. There may have been spatial reallocation of residential sector emissions with people moving away from urban centres to villages/suburbs. This is why many cities across the globe are showing improvement in some of the air pollutant concentration levels leading to a widespread belief that all air pollutants have decreased everywhere.

3. What are some recent findings and studies about air pollution and respiratory problems in our part of the world? What does it mean for the region’s response to the current pandemic?

There have been numerous studies linking air pollution and health. A World Health Organization report published in 2016 reports approximately 1.8 million deaths in the eight HKH countries just due to ambient PM2.5 pollution. So we know that there is a strong correlation between poor air quality and human health. Recently, there have been several scientific papers from Europe and US that have co-related COVID-19 with ambient air pollution. A paper from Harvard School of Public Health correlates higher COVID-19 mortality rates in places that have higher ambient air pollution levels in the US. Similar co-relation is also found in studies from Northern Italy and England. Studies have also found SARS-CoV-2 virus in ambient aerosol particles measured in Italy. One study found detectable levels of the virus inside a hospital in China while another study did not find any evidence of the virus in a hospital indoor air inside Iran. There is a study published which co-relates higher mortality rates due to COVID-19 with meteorology.

I am not aware of studies from South Asia co-relating COVID-19 with bad air quality but would assume that impact of COVID-19 would be stronger on populations already susceptible with exposure to bad air quality that we have in the region.

4. The current situation is unprecedented. As an atmospheric scientist, what are your thoughts on this rather unprecedented situation and being able to study what was otherwise a purely hypothetical scenario? Is there anything that has surprised you?

The current halt of transportation and industrial activities, is unprecedented from a global and regional perspective. However, our region has experienced situations like these in the past, albeit for short durations, often due to political turmoil. Transportation and industrial strikes or shutdowns, popularly known as “bandhs” do mimic situations like the one we are experiencing now. What is unprecedented, however, is that it is occurring across a wider region and over an extended period of time. There have been several peer-reviewed scientific papers in the past discussing the effect of short-term bandhs on local air quality.

As for being surprised, no, I haven’t been surprised by the overall reductions in air pollution but I have been very excited by this unprecedented opportunity to look into the different roles different sources play in the overall picture of air pollution in the HKH. As I mentioned before, the residential sector is the biggest contributor to air pollutants in the region and this has not changed significantly. However, given the reallocation of pollutant emissions both in the source sector and source region, there have been illustrations of how good the air quality can be if air pollution is addressed sustainably. We have all seen this ourselves and there have been some media reports of being able to see Mt. Everest from Kathmandu, views of the Himalayas from the Punjab region of India after 30 years, and clear images of cityscapes circulated in the news and social media, which are in some sense pleasant surprises and reminders of attainable air quality. The situation has thus provided an opportunity for advocates of cleaner air quality to explain to the general public with evidence what they are missing and what is possible.

5. Are there new questions or unknowns that this situation has raised for the field of atmospheric science and pollution studies? What are some of them?

Air pollution mitigation has always been a complex problem to tackle. Mitigation has to address multiple sources, where multiple government departments and agencies have jurisdiction for mitigation action measures, and has always required trans-disciplinary experts to work together to come up with solutions. This current lockdown situation, although it may seem simple to the general public, has demonstrated to scientists the complexity of the problem and has reinforced that there is no one simple solution. Complete reductions from the transport sector did not resolve the issue for example. Although it has demonstrated possible reductions, it has also raised questions about durability of the solution and the need for reductions across sectors for sustainability. The transportation sector is transforming itself and offering cleaner transport and mobility solutions such as electric vehicles. The industrial sector is already more regulated compared to other sectors.

The current situation has allowed us an opportunity to address a sector that has long been avoided by the general public and decision makers. This is the residential sector. Our laws and mitigation efforts have primarily focused on controlling emissions from the transport and industrial sectors. We have to tackle the emissions from the residential sector if we really want to improve air pollution and its exposure in our region. Emissions inventories have always pointed to strong contributions from the residential sector in the HKH region. However, apart from small projects to improve the energy efficiency of cook stoves and access to cleaner fuels there has not been a strong push to tackle air pollution from the residential sector. The challenge has been to recognize and prioritize this as a sector to tackle because of the scale of mitigation interventions and investments that would be required.

Of course, there are numerous other technical questions like why certain pollutants such as ozone did not decrease during this time. We will explore them in the days to come.

Stay up to date on what’s happening around the HKH with our most recent publications and find out how you can help by subscribing to our mailing list.

Sign Up